Scientists have figured out a way to detonate the ‘doors’ that lead to the heart of cancerous tumors, blowing them wide open for drug treatments.

The strategy works by triggering a ‘timer bomb’ on the cells that line a tumor’s associated blood vessels.

These vessels control access to the tumor tissue, and until they are opened, engineered immune cells can’t easily gain entry to the cancer to fight it off.

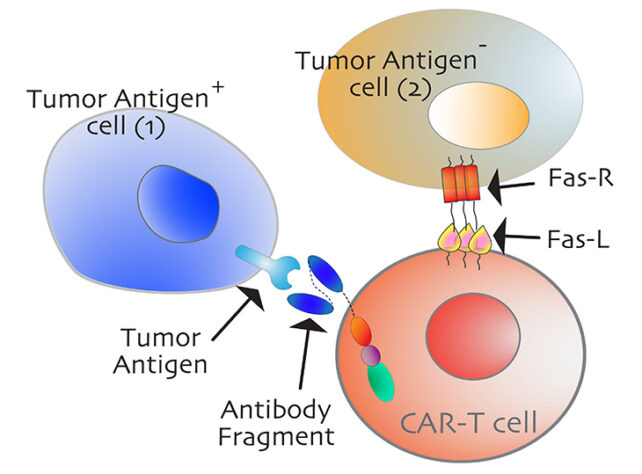

The timer bomb on these cells is actually a ‘death’ receptor, called Fas (or CD95).

When activated by the right antibody, it triggers the programmed death of that cell.

Scientists at the University of California, Davis (UCD) and Indiana University argue that until recently, Fas has been “undervalued in cancer immunotherapy”. To date, not one Fas antibody has made it to clinical trials.

In recent experiments using mouse models and human cell lines, scientists at UCD have at last identified specific antibodies that, when attached to Fas receptors, effectively trigger self-implosion.

“Previous efforts to target this receptor have been unsuccessful. But now that we’ve identified this epitope, there could be a therapeutic path forward to target Fas in tumors,” explains immunologist and senior author of the study Jogender Tushir-Singh.

The antibody that binds to this epitope (a specific part of the death receptor), essentially represents the kill switch for the cell.

Once this immune checkpoint is blown open, other cancer therapies, like CAR-T therapy, can gain access to more of their targets, which are often clumped together and hidden within the tumor.

CAR-T therapy works by programming a person’s own white blood cells, called T-cells, to bind to and attack specific types of cancerous cells.

These tailored immune cells, however, cannot usually get past the ‘bystander’ cells that lack the recognisable antigens usually used to target tumor cells.

As a result, CAR-T therapy has only been approved to treat blood cancers or leukemia. It fails to provide consistent success against solid tumors.

“These are often called cold tumors because immune cells simply cannot penetrate the microenvironments to provide a therapeutic effect,” explains Tushir-Singh.

“It doesn’t matter how well we engineer the immune receptor activating antibodies and T cells if they cannot get close to the tumor cells. Hence, we need to create spaces so T cells can infiltrate.”

In recent experiments at UCD, scientists developed two engineered antibodies that were “supremely effective” at attaching to Fas receptors and causing bystander cells to self-implode. This was true in ovarian cancer models and many other tumor cell lines tested in the lab.

The Fas ligand developed by researchers was able to engage two critical parts of the Fas receptor, which researchers say should be investigated further. These parts hold potential as future drug targets.

If CAR-T cells can one day be engineered to target these receptor parts on bystander cells as well, the therapy could be much more effective against tumors.

“We should know a patient’s Fas status – particularly the mutations around the discovered epitope – before even considering giving them CAR-T,” says Tushir-Singh.

“This is a definitive marker for bystander treatment efficacy of CAR-T therapy. But most importantly, this sets the stage to develop antibodies that activate Fas, selectively kill tumor cells, and potentially support CAR-T-cell therapy in solid tumors.”

The study was published in Cell Death & Differentiation.

Source: Science Alert